At least this is what the looters thought. We should now all know the most apt way to describe this dubious form of collection – and it’s a word that has historical resonance: vandalism.

So many antiquities were stolen that they fill massive imperial museums in many of the world’s capital cities: the British museum, the Louvre, the Metropolitan, the Istanbul museum. These institutions continue to hold on to national treasures of other countries, claiming that they are international museums keeping the heritage of the world and making it available to everyone.

So it is with the Parthenon Marbles – one of the most controversial acts of vandalism of them all – held in the British Museum in London after being dubiously “acquired” by Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin in 1801, less than three decades before the independence of Athens from Ottoman rule.

The UK’s opposition leader, Jeremy Corbyn, recently stated that a Labour government would return the marbles to Greece. In a statement on June 3 he said:

As with anything stolen or taken from occupied or colonial possession – including artefacts looted from other countries in the past – we should be engaged in constructive talks with the Greek government about returning the sculptures’

The traditional position for the British government on the Parthenon marbles is that it is up to the trustees of the British Museum to decide on the return of any artefacts in its collection. But, as the government is a key funder of the museum, it can surely wield a powerful influence on trustees’ decisions.

So the marbles have remained in London. And the antiquities trade is still going strong – not only depriving countries of their heritage, but, which is worse, depriving the world of the information that could be extracted with appropriate systematic excavation and reducing the artefacts into mere art pieces that can only be enjoyed in a stale museum context and not as both rich symptoms and teachers of the history of mankind.

Meanwhile, there is evidence that revenue from the sale of stolen antiquities looted in Syria and Iraq has been used to fund Islamic Stateand other terrorist groups – so one illegal activity has been connected to many others.

Fighting the trade

How are we to stop this trade, which is a scourge of historical knowledge, local pride and international sovereignty. The illicit trade in antiquities – and almost all trade of antiquities is illegal in some sense, as it almost always breaks the law of the source countries – is considered to be a common crime. In many countries there are police departments that are specialised in this type of crime. For example, the UK has the Metropolitan Police’s art and antiques unit and in the US the FBI has a 16-person Art Crime Team.

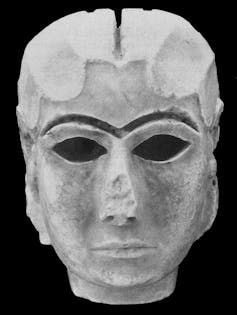

The Mask of Warka, one of the earliest representations of a human face, was recovered in Iraq after being stolen from the National Museum in Baghdad during the 2003 US invasion.

In the UK, “Operation Bullrush” by the art and antiques unit successfully prosecuted dealer Jonathan Tokeley-Parry in 1997 for smuggling priceless antiquities out of Egypt (he was also sentenced in absentia in Egypt). Meanwhile in 2002 a US court convicted Frederick Schultz, the former president of the National Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art, under the 1934 National Stolen Property Act (NSPA) of conspiracy to receive antiquities stolen from Egypt.

Meanwhile various countries are signing memoranda of understanding (MOU) to control the importation of antiquities and to coordinate efforts to prevent smuggling. In 2017 the US concluded an MOU with Egypt. These arrangements are backed by the 1970 UNESCO Paris convention which prohibits the sale and purchase of ancient art that had not been in circulation before the ratification of that treaty by each country.

But most of these measures and stakeholders focus on the final destination of the illicit antiquities, the collectors or museums – and this isn’t enough. There need to be measures to account for all stages of the illicit trade of antiquities: from excavation to the first and second intermediary (the dealers), to those transporting it from one country to another, to the final purchaser, the collector.

Working together

The Heritage Management Organisation (HERITΛGE), a project associated with the University of Kent, has been working to create a comprehensive strategy for the illicit antiquities trade, which aims to combine the knowledge and efforts of multiple stakeholders: scientists, local communities, police, collectors, legislators and the public.

An exhibition of Iraqi antiquities, including many that had been looted during the US invasion and recovered, co-funded by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the Iraqi government. EPA-EFE/Ahmed Jalil

To prevent illicit excavations police forces need to deploy the latest technological advances such as satellite surveillance, pattern recognition and forensic science. But they need the assistance of local communities in areas of archaeological significance who need to become more positive as stakeholders in the protection of their heritage.

Collectors should not all be seen as the enemy – but as potentially powerful stakeholders that need to be engaged and trained in the fight against the illegal antiquities trade. Many collectors are careful in how they buy – but others are simply ignorant of how to buy more responsibly. Collectors have insights and valuable information on clandestine networks, art dealers and their potentially rigorous verification (or not) of the legal standing of each piece in their own collections. With the cooperation of the Greek Ministry of Culture, HERITΛGE organised the first ever meeting between collectors, the ministry and the police in Greece. Much more needs to be done in this area.

It’s all very well having international treaties to control the antiquities trade, but first they must be understood by all the relevant stakeholders. HERITΛGE has published one of the few commentaries on restitution in both European and international Law.

It is imperative that volunteers are trained on how to check the provenance of items for sale and on how to use existing databases to “catch” clandestine or stolen pieces. One example is academic Christos Tsirogiannis who had had some success in tracking down looted antiquities and ensuring they are returned to their country of origin.

But, for this strategy to bear fruit, all the relevant stakeholders need to collaborate with an open mind and then maybe there is a chance that we’ll be able to bring an end to millennia of the despoiling of so many countries’ national heritage.

#HeritageNation

Written by Evangelos Kyriakidis, Senior Lecturer in Aegean Prehistory, University of Kent and director of the Heritage Management Organization.

Giannis Grammatikakis is a conservation scientist with an MSc in environmental chemistry and a PhD in inorganic chemistry.

Giannis Grammatikakis is a conservation scientist with an MSc in environmental chemistry and a PhD in inorganic chemistry.