: Uncategorized

Europe Mapping: Survey

HERITΛGE is delighted to announce our inaugural survey aimed at mapping the training needs of European Heritage Managers.

This is your chance to actively influence the design of training workshops, summer schools, and academic certificates that we offer to heritage professionals. Your input will assist us in comprehensively understanding the capacity and requirements of the European Cultural Heritage Sector. Moreover, it will provide us with the necessary data to collaborate within our organization and with partners, governments, and international organizations to create more training opportunities that align with the skills you need and desire for effective cultural heritage management.

We are initiating a campaign to gather insights into the themes and topics that resonate with you, empowering us to develop future training courses that make a significant impact. Your participation, whether as an active or aspiring heritage professional, holds immense value.

Kindly take a few moments to fill out our survey and share your thoughts on how our training programs can assist you in overcoming challenges or adopting new working methods. The survey, designed to take no more than 10 minutes, will remain open for responses until December 31st.

We eagerly anticipate your contribution to our endeavors as we strive to best address the training needs of cultural heritage professionals in Europe.

Empowering heritage managers to transform visits into memorable experiences

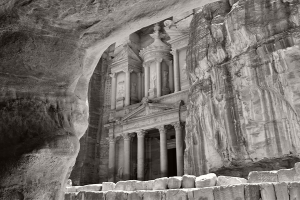

We’re excited to share the highlights of our recent 3-day online workshop on “Heritage Interpretation for Site Managers”, which took place from 6 to 8 October 2023. Our workshop is designed to equip heritage managers with the skills to transform any visit into an unforgettable experience by crafting meaningful experiences for visitors.

This year’s transformative workshop brought together 16 passionate heritage managers from Africa (Cape Town, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, South Sudan, Zimbabwe) and Asia (Iraq, Saudi Arabia) for a deep dive into the principles and practices of high-quality heritage interpretation.

Led by the experienced interpretive trainer and planner, Valya Stergioti, the workshop provided participants with a comprehensive understanding of key concepts in heritage interpretation, planning, and thematic development. Valya, with over 20 years of expertise in organizing interpretive workshops, guided participants through interactive exercises and assignments, fostering a dynamic learning environment.

The participants not only acquired the techniques of formulating themes for tangible and intangible heritage phenomena but also explored the importance of engaging local communities in the interpretation process. The workshop aimed not just to impart knowledge but to empower heritage managers to transform heritage phenomena into experiences. Participants left the workshop feeling equipped to address the diverse needs of visitors through interpretive media.

The workshop featured a guest lecture by Dr. Lena Stefanou, an archaeologist and manager of our programs in Ghana who specialises in museum and heritage studies. Dr. Stefanou shared valuable insights on the theory and practice of museum studies, museum education, and the management of cultural heritage. Her expertise extends to community archaeology and heritage programs, emphasizing the vital role of community engagement in preserving and promoting our shared heritage.

Looking Ahead: Follow-Up Tutorial and Continued Learning

To ensure ongoing support and development, participants had the opportunity to engage in a follow-up tutorial with Valya Stergioti on 16 October. This session gave participants the opportunity to seek advice, ask questions, and receive guidance on upgrading their final assignments. This commitment to continuous learning reflects our dedication to nurturing a community of skilled and passionate heritage managers. As we continue to empower professionals in the field, we look forward to witnessing the positive impact they will have on preserving and promoting our global heritage.

Culture as a driver of sustainable development in Greece: a new report

HERITΛGE is pleased to announce the publication of an important report for the future of Greece’s cultural sector titled “Culture in Greece: How the culture sector can become an agent of sustainable development and a source of social value”, featuring a contribution by HERITΛGE Director Dr. Evangelos Kyriakidis.

The report was commissioned by DiaNEOsis, an Athens-based think tank that aims to contribute to public discourse on social and economic issues and promote change and meaningful political reform in the country.

It will be presented during the “Culture: Our Comparative Advantage” event organized to celebrate 70 years of the Friends of Music Society. The event will take place at Megaron, the Athens Music Hall, founded and managed by the society on Wednesday, October 18th.

The diaNEOsis report attempts a mapping of Greece’s cultural sector. It explores a number of themes, including the ways culture can contribute to the production of social and economic value and what Greece can do to strengthen its cultural and creative industries so that they can serve as a lever for sustainable development and regional revitalization.

The research aspires to open up a series of discussions and new research endeavors focused on the role of culture in today’s Greek society and economy. In this context, the writing team, headed by Christos Karras, a Cultural Strategy Consultant & Senior Consultant at the Onassis Foundation, focuses on eight areas and concludes with specific proposals that could form the basis for targeted, development-focused cultural policies.

The report’s authors also include: lawyer Gerasimos Yiannopoulos, Cultural Diplomacy researcher Olga Kolokytha from Universität für Weiterbildung Krems, researcher Antigoni Papageorgiou from Panteion University of Social and Political Science, journalist and museologist Dimitris Trikas, Onassis Foundation Digital Development and Innovation director Prodromos Tsiavos, and Benaki Museum curator and museum and cultural development advisor Sophia Chandaka.

Strengthening Partnerships: HERITΛGE visit The Gambia

An extended HERITΛGE team was in The Gambia in August to assess the progress of the Organization’s capacity development initiatives and explore how local communities are taking on board the heritage management training. HERITΛGE’s HerMaP Gambia program has delivered in the past three years, including HERITΛGE’s Training of Trainers (ToT) program that has been disseminating knowledge, and strengthening relationships with key stakeholders who play a vital role in cultural heritage management.

“Meeting with stakeholders underscored the effectiveness of our training programs in empowering trainers to pass on their knowledge to a broader audience in the Gambia,” says Mina Morou, HERITΛGE’s Africa Projects Manager. “To build on this success, we have scheduled another cycle of the “Train the Trainers” program for this autumn, aiming to continue expanding the reach of heritage management education in the region.”

During the visit, our team was happy to reconnect with a range of existing partners and new ones, who play pivotal roles in heritage management and preservation in The Gambia. These include the Institute of Travel and Tourism of The Gambia (ITTOG), the National Centre for Arts and Culture (NCAC), the National Assembly and the Gambia Tourist Board, EU Delegation, the Juffureh Albreda Youths Society (JAYS), My Gambia, National Environment Agency (NEA) and more.

HERITΛGE is also happy to announce that our new Gambian office in Banjul is now operational and will soon start hosting activities.

The program is co-funded by the European Union.

SHIFT Project forges ahead to make heritage accessible through technology

HERTΛGE attends SHIFT Consortium meeting: consulting stakeholders and reviewing use cases to make cultural heritage more accessible and inclusive through technology.

The SHIFT Consortium held its second in-person meeting earlier this month in Knjaževac, Serbia. HERITΛGE and twelve consortium partners were hosted on 15th – 16th June by the Homeland Museum of Knjaževac, part of the Balkan Museum Network.

¨We had a great opportunity to take stock of all the progress that has already been made for the creation of tools that will help make cultural heritage more accessible and inclusive,” said Razvan Purcarea, from project coordinating partner SIMAVI.

SHIFT is funded by the European Commission’s Horizon Europe program. It brings together 13 leading research and industrial organisations and SMEs with a common vision: to strengthen the impact of cultural heritage assets. SHIFT will produce an array of tools taking advantage of the latest developments in fields such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), Haptics, and Auditory Synthesizers to increase the appeal of historical artefacts, improving their accessibility and usability for everyone through better content representation, enriched user experiences, inclusive design, training, and more engaging business models.

During the Knjaževac consortium meeting, partners had the opportunity to review use-case scenarios and functional requirements, engage with external stakeholders, and attend the opening of the Homeland Museum’s latest exhibition.

HERITΛGE Community Engagement Workshop in Rwanda: Empowering Heritage Managers and Tourism Stakeholders

HERITΛGE is happy to announce the completion of its first in-person, 3-day training workshop in Rwanda, organised in partnership with the Rwanda Cultural Heritage Academy (RCHA) .

28 stakeholders took part in the Community Engagement for Heritage Management workshop on 29-31 May, led by HERITΛGE Director, Dr. Evangelos Kyriakidis. During the workshop, heritage managers and tourism stakeholders were given the tools and knowledge to enhance community involvement in preserving and promoting cultural heritage with a view to also enhancing sustainable tourism development.

“We would like to thank Dr Kyriakidis for sharing his incredible knowledge with us,” said Ambassador Robert Mazorera, RCHA’s Director General. “ It was an awakening course for us in relation to local community engagement in line with heritage management. ”

Dr. Kyriakidis noted that HERITΛGE’s first in-person workshop in the country is an important milestone for the organization. “It was great honour to visit Rwanda and to witness the very strong efforts being made across communities to preserve and strengthen local heritage,” Dr. Kyriakidis said. “HERITΛGE will continue to provide training and support heritage managers in working with RCHA to transform Rwanda’s heritage assets into dynamic sources of learning, community identity and sustainable economic development.

The workshop is part of HERITΛGE’s HerMap – Africa Program which has received funding from the Mellon Foundation’s Humanities in Place program.