: Conservation

Capacity-Building for Libraries and Archives in Iraq

HERITΛGE delivered an in-person workshop in Bagdad for the Preservation of Libraries and Archives in Iraq project. The project is realised in cooperation with The Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TARII) and supported by a grant from the American Embassy in Iraq.

It aims to strengthen the capacity of custodians of libraries and archives in Iraq and ensure the trainees can independently handle the development and management of preventive conservation projects for their institutions.

The training forms part of HERITΛGE’s broader commitment to strengthening cultural heritage resilience in regions affected by conflict and environmental pressures.

The workshop, held from 18-29 January, was delivered by Mohammad al-Mimar, Nil Baydar, Maja Kominko, Nikolas Sarris, in cooperation with the Iraq National Library and Archive. It provided instruction in Preventive Conservation, Project Development, Project Management and Fundraising .

Attended by 30 participants, the training introduced key concepts including bookbinding components and terminology, handling of archival materials, causes of paper and book deterioration, environmental control in libraries and archives, and first-aid conservation for paper artefacts.

Participants also explored environmental monitoring and data analysis, emerging environmental challenges, and risk management strategies through practical exercises. Depending on the module, trainees worked individually or in small groups of three to four participants to apply their learning.

Hands-on sessions were complemented by three study visits, one of which was to the private archive of Ahmad Sousa and another to the Imam al Husayn Shrine in Karballa, designed to showcase the preservation issues in a private archive and a religious library respectively.

A third visit took the trainees to the UNESCO World Heritage Site in Samarra, where they had the opportunity to explore challenges in preservation, especially dealing with previous heavy-handed restorations, and to discuss international conservation standards and practices.

Training Begins in Iraq to Strengthen the Preservation of Libraries and Archives

Training has commenced in Baghdad under the project Preservation of Libraries and Archives in Iraq: Building Capacity for Preventive Conservation, implemented by HERITΛGE in partnership with The Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TARII) and the National Library and Archives of Iraq, with the support of the U.S. Embassy in Iraq.

Training has commenced in Baghdad under the project Preservation of Libraries and Archives in Iraq: Building Capacity for Preventive Conservation, implemented by HERITΛGE in partnership with The Academic Research Institute in Iraq (TARII) and the National Library and Archives of Iraq, with the support of the U.S. Embassy in Iraq.

A two-week specialised training course in document and archive preservation and management is currently underway at the National Library of Iraq. The training aims to strengthen the scientific and professional capacities of librarians and archivists, with a particular focus on preventive conservation and internationally recognised standards for the care and management of documentary heritage.

The course is delivered by an international team of experts, led by HERITΛGE’s Nicholas Saris and Maja Kominko. Through a combination of lectures and applied training, participants are introduced to practical conservation methodologies adapted to the Iraqi context.

Beyond technical training, the programme places strong emphasis on sustainability and institutional empowerment. Participants will develop and implement preservation projects within their respective institutions, supported by mentoring from the project team. The initiative also seeks to foster a national professional network, facilitating long-term knowledge exchange and cooperation among custodians of Iraq’s documentary heritage.

Through this project, HERITΛGE and its partners reaffirm their commitment to supporting the National Library and Archives of Iraq in its leading role in safeguarding the country’s documentary collections and strengthening the capacities of heritage professionals to preserve Iraq’s national memory for future generations.

Milestone project to preserve Buddhist Heritage in Pakistan completes phase 1

HERITΛGE is proud to announce the completion of the first phase of the ‘Preservation of Buddhist Rock Reliefs in the Swat Valley: Documentation, First Aid Conservation, and Climate Change Adaptation‘ project, realised in collaboration with EssaNoor Associates, the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums KP, and the Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan, and made possible thanks to the support of the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund.

HERITΛGE is proud to announce the completion of the first phase of the ‘Preservation of Buddhist Rock Reliefs in the Swat Valley: Documentation, First Aid Conservation, and Climate Change Adaptation‘ project, realised in collaboration with EssaNoor Associates, the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums KP, and the Italian Archaeological Mission in Pakistan, and made possible thanks to the support of the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund.

Swat Valley in northern Pakistan is home to some of the most significant remnants of the ancient Gandhara civilization. Among these are Buddhist rock reliefs and inscriptions, likely carved in the 7th or 8th century BC, which are now under threat from natural erosion, human activity, and the escalating impacts of climate change.

In response to these emerging challenges, the project adopted a multi-phase strategy encompassing digital documentation, emergency conservation, local capacity development, sustainable tourism, and climate resilience initiatives.

Through extensive field surveys, the project digitally recorded 78 Buddhist rock reliefs using high-resolution photography, 3D scanning, and interactive geographic mapping. Emergency stabilization measures were also carried out at several vulnerable sites, providing necessary ‘first aid’ to prevent further deterioration. A major milestone was the launch of the project website, which offers free access to 3D models, maps, and comprehensive documentation of these heritage sites. The platform supports research, education, and site management while promoting global engagement with Swat’s rich cultural heritage.

The local communities and institutions were engaged throughout the project to raise awareness and empower them to become custodians of these invaluable heritage sites through grassroots discussions and workshops. Thirteen heritage professionals and seven local community members were trained in digital preservation skills to ensure that the knowledge and tools for conserving the heritage are sustained locally, empowering the community to manage and protect their own cultural resources. The project also recorded six oral testimonies, preserving the intangible heritage of the local community. These stories reflect the lasting impact of Buddhist influence in the Swat Valley, highlighting traditional crafts like Gandharan wooden art, stone masonry, and shawl embroidery, which have been inspired by centuries of Buddhist heritage.

In addition to heritage conservation, the project identified sustainable tools for both preservation and economic development. The development of hiking trails and eco-tourism facilities was proposed to promote local tourism and provide sustainable income for rural communities. Alternative livelihoods through eco-tourism, local crafts, and medicinal plant cultivation are also encouraged by the initiative that aims to ensure economic stability in the region.

Closing Ceremony

The Swat Museum hosted a project closing event on 15 April 2025, attended by approximately 200 people, including students, heritage practitioners, local community representatives, and international experts. The ceremony included a presentation by project team, detailing the objectives and accomplishments, as well as the official launch of the website. A panel discussion, chaired by HERITΛGE’s Dr. Maja Kominko, gathered professionals from both the academic and grassroots communities. The panel addressed the cultural significance of Buddhist heritage in Swat, the significance of community participation in conservation, and the adaptation to the impacts of climate change on heritage.

The Swat Museum hosted a project closing event on 15 April 2025, attended by approximately 200 people, including students, heritage practitioners, local community representatives, and international experts. The ceremony included a presentation by project team, detailing the objectives and accomplishments, as well as the official launch of the website. A panel discussion, chaired by HERITΛGE’s Dr. Maja Kominko, gathered professionals from both the academic and grassroots communities. The panel addressed the cultural significance of Buddhist heritage in Swat, the significance of community participation in conservation, and the adaptation to the impacts of climate change on heritage.

The guests were guided through a thoughtfully curated exhibit showcasing the project’s key outputs, including photographic documentation, interactive maps, and 3D-models. Team members were present to explain the conservation methods employed throughout the project and to demonstrate the digital equipment used in the preservation process. The ceremony concluded with the presentation of shields and certificates to honor significant contributions. Project stakeholders and members of the public reaffirmed their commitment to safeguarding Swat’s cultural heritage for the benefit of future generations.

The ‘Preservation of Buddhist Rock Reliefs in the Swat Valley’ project underscores the increasing significance of integrating digital technologies, emergency conservation, community engagement, sustainable tourism, and climate resilience into contemporary heritage conservation practices. It also serves as a model for future initiatives aimed at safeguarding vulnerable cultural heritage sites.

For additional information and access to digital documentation, visit www.heritageofswatvalley.com.

Preserving Shibam’s Heritage: A New Museum Takes Shape

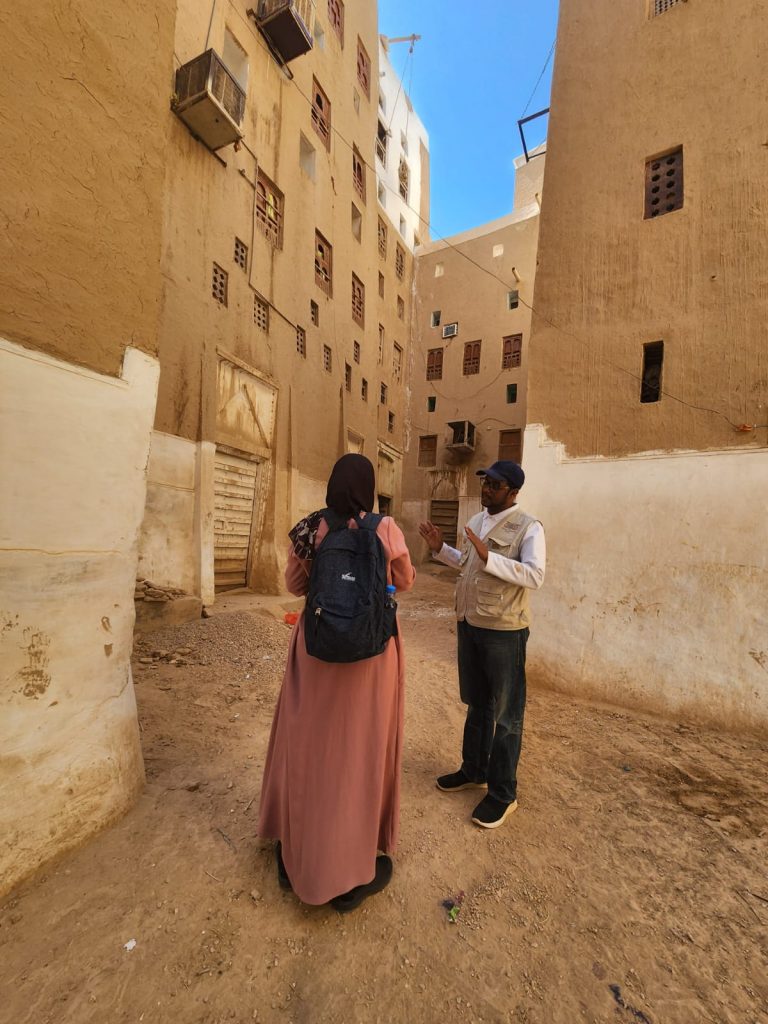

A major step was taken in early February to safeguard the rich cultural heritage of the city of Shibam in Yemen, in the framework of the Preserving the Unique Earthen Architecture of Shibam project, funded by the ALIPH Foundation, is implemented by The Heritage Management Organization (HERITΛGE) in partnership with the American Foundation for Cultural Research (AFCR) and the General Organization for the Preservation of Historic Cities in Yemen (GOPHCY – Shibam).

Museum experts Shatha Safi and Khulod Najjar visited Shibam to guide the community-led design and planning of a brand new museum to be created by the project.

Old City of Shibam: a World Heritage Site

The walled City of Shibam is one of the oldest examples of urban planning based on the principle of vertical construction with impressive tower-like structures Following years of crisis brought about the war in Yemen, compounded by and the impact of climate change, this unique UNESCO World Heritage Site is facing significant challenges.

The proposed museum project addresses a request from the General Organization for the Preservation of Historic Cities in Yemen (GOPHCY) to create a centralized space that will bring together collections currently dispersed across several venues in the city. In addition to exhibiting Shibam’s history and artifacts, the museum will feature spaces dedicated to traditional arts and crafts, fostering cultural preservation and engagement. Furthermore, a dedicated room equipped with video-conferencing facilities will enable local residents to participate in online training and conferences. To ensure the sustainability of this training venue, the project will install solar panels and an internet connection, providing continuous access to digital resources.

The experts’ visit marked a crucial phase in the project; three key meetings were held to align the museum’s vision with community expectations and institutional support.

The first meeting focused on establishing a framework for the creation and operation of the museum. It brought together Hassan Aideed– Director General of GOPHCY – Shibam, the Local Committee for Museum Preparation, Hedaya Ghraibeh, Project Manager for HERITΛGE with the two visiting experts. Discussions revolved around how the museum can authentically represent Shibam’s history, traditions, and way of life while aligning with the aspirations of the local community. The experts emphasized the importance of preserving both the material culture—such as architectural heritage—and the stories, customs, and knowledge passed down through generations.

The second meeting allowed the project team, the visiting experts, and GOPHCY-Shibam to discuss the museum with Tariq Falhum, Director General of Shibam District and his team. This discussion highlighted the role of local authorities in supporting the museum’s development and ensuring its long-term sustainability. By integrating the museum into the broader heritage conservation strategy for Shibam, the project aims to strengthen both cultural preservation and community engagement.

The third meeting was held in coordination with the Women’s Development Administration at the District Office. This session brought together 15 women and girls from diverse backgrounds, including home-based workers, recent graduates, shopkeepers, and others, to discuss the evolution of traditional practices and contemporary lifestyles in Shibam. The conversation explored the challenges faced by women and the transformation of their position in society over time, providing valuable insights into the social and cultural shifts within the community.This meeting plays a vital role in ensuring that the museum accurately represents the experiences, voices, and contributions of women to Shibam’s heritage and daily life.

As the planning and design process continues, Shibam is moving closer to having a dedicated space that tells its story and brings the local community together.

The project provides practical, on-the-job training for heritage professionals in Shibam, ensuring that conservation efforts are sustained by skilled local experts. Currently, four trainees are already working alongside our architects and engineers on the documentation process for the South Palace, where the museum will be located.

The Preserving the Unique Earthen Architecture of Shibam project also includes architectural and infrastructure assessments in the first year, along with an in-depth study on climate action, proposing sustainable strategies for both Shibam and Wadi to ensure long-term resilience and preservation.

New Training Calendar: Online Workshops for Heritage Managers

The Heritage Management Organization (HERITΛGE) is happy to announce a series of online training workshops for heritage professionals and caretakers for 2024-2025. A variety of scholarships and funding opportunities are available. As places are limited, candidates are advised to apply as soon as possible.

The Heritage Management Organization (HERITΛGE) is happy to announce a series of online training workshops for heritage professionals and caretakers for 2024-2025. A variety of scholarships and funding opportunities are available. As places are limited, candidates are advised to apply as soon as possible.

Online Workshop Calendar 2024-2025

Introduction to Heritage Interpretation for Site Managers | 01–03 October 2024

Master the principles of high-quality heritage interpretation and gain hands-on experience in implementing them at your site/organization in order to create meaningful and unforgettable experiences for visitors.

Engaging Communities in Cultural Heritage | 11–13 October 2024

Understand the community engagement process, a key heritage management strategy. Master the challenges of working with local communities discern between communities and audiences and understand audience segmentation, get introduced to ethnographic approaches to creating collaborative research-based programs, and learn the methods and techniques of oral history to elicit and document tangible and intangible heritage.

Conservation III: Preventive Conservation (pilot) | 15-17 November

A pilot workshop only open to heritage managers that have previously completed Conservation II: First Aid for Finds.

Interpretive Writing for Natural and Cultural Heritage | 25–27 November 2024

Learn how to write text that grabs and holds the reader’s attention. Discover and practice a wide range of techniques to engage visitors and master the techniques of interpretive writing. Participants will work to become a HERITΛGE-accredited Interpretive Writer, after successfully completing, and being assessed on, the exercises and activities.

Project Management for Heritage Managers | 13-15 December 2024

Gain the skills and knowledge to run a successful project from inception, through the planning and implementation phases to closure. Create a work breakdown structure, a critical path diagram and a Gantt chart. Research potential funders and write a grant application. Improve personal time management skills. Learn to think critically, identify risks and create solutions.

Organising Temporary Exhibitions from your Collections and Touring Strategies | 14–16 February 2025

The focus of this workshop is to give you the skills to ensure temporary, touring and partnership exhibitions can enhance and promote your institution’s mission, create new audiences and mutually beneficial partnerships. Attendees are encouraged to bring their own exhibition ideas to the workshop for discussion and development.

Communication Strategy and Strategic Marketing for Cultural Organizations | 07-09 March 2025

Join a focused learning experience that provides a systemic approach to successfully attract key audiences’ attention through traditional, new, and social media. Acquire a working guide to effectively communicate news, initiatives, and announcements of your organization and manage communication around a crisis or issue.

Successful Fundraising for Heritage Managers: Strategies and Best Practices | 28-30 March 2025

Start-up and build an organization’s contributed revenue to increase its impact in the world. Participants learn best practices and apply them to create the case for support and letter of inquiry for their own organization or project. Workshop sessions combine live and asynchronous lectures, case studies, class discussions and interactive exercises.

Conservation I: Introduction to the General Principles of Cultural Heritage Conservation | 4-6 April 2025

Learn the fundamentals, the ethics, the evolution, and the contemporary international context of conservation. At the end of the course, participants will be able to understand the potential of conservation, together with the processes which are necessary to maximize it.

Strategic Planning for Heritage Managers | 9-11 May 2025

Successful strategy can lead to success and this course will provide participants with the tools and methodologies to successfully formulate and implement strategy in organizations managing cultural heritage. Learn the methods and tools of strategic analysis that will enable you devise and evaluate alternative strategic choices and comprehend the demands of a strategy implementation project.

More workshop dates will be announced soon. To apply visit our Executive Leadership Training page.