: Uncategorized

"Hidden Landscapes of Heritage Productions" by Vassia Hadjiyannaki

As I sit down to write a few words about my experience in producing and filming a documentary on landscape archaeology in the island of Naxos, I wonder what could be of interest to us, the heritage tribe…

I am a producer/director with an MA in Heritage Management, working for Greece’s national broadcaster ERT, as well for the Heritage Management Organization.

I specialize in documentaries on heritage, anthropology and on children’s programs.

This documentary came about by sheer chance, actually.

My first intention was to gather information for another heritage production, this one for children. But the latter was at an initial stage of conception and the team consisted of just me and the artistic director.

The documentary on Naxos, on the other hand, would be the result of a research taking place for quite some time on location, conducted by the Mc Cord center for History, Classics and Archaeology of the University of Newcastle, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Oslo and the Ephorate of Antiquities of Cyclades.

First point to note:

If you are a heritage manager from the production field, you will be needing a solid research/scientific team to work with; mostly because this is the way to guarantee authenticity and support, scientific and financial. Without those, the road is long and it

won’t necessarily come to fruition, even if it is well researched by the production team and vice versa.

The next step was to bring the McCord center’s scientific team for the research in Naxos, together with the production and management team from Greece’s National Broadcaster (ERT), and form – more than a coproduction- a synergy.

Second point to note:

Funding for heritage documentaries can be difficult these days. Hence, forming some sort of a co-production or synergy is essential in order to get the better of two worlds.

An agreement was established and the pre-production begun, including the values to be communicated, the narrative, the artistic style, days of filming, crew, cost etc. The scientific and the production team worked closely together, to make sure we were both aiming towards the same direction.

Third point to note:

Once the production team is formed and the concept of the narrative is designed, one needs to start thinking of:

- The target audience

- The uses for this production (academic, educational, edutainment etc)

- The distribution (media, conferences, workshops and other venues)

This point will guarantee that when the crew is on location for the filming, the human and financial resources available for the production will be used up to the optimum potential in accordance with the desired goals.

Fourth point to note:

Once on location, the production team – apart from filming- is also doing another very important work; namely engaging with the local society. We need to always keep in mind that television production is a popular medium. So these productions, on location and upon distribution, approach the local society, stakeholders and the target audience, in a completely different way. This connection creates another type of bond with the people and should be part of the production design, one of its main goals.

All points completed, and a year later, the documentary was aired twice by Greece’s national broadcaster ERT. The first time was scheduled and the second occurred as a result of the audience’s demand!

On May the 15th a workshop took place at the University of Newcastle, with the title:

“Filming the Past in the Present: Heritage and Documentary Practice”

It was a collaborative event supported by the Digital Cultures Research Group and the Research Centre for Film, the Cultural Significance of Place Research Group.

There were three films presented by the research teams and the producers. One of them was Hidden Landscapes of Naxos.

All the films were completely different in artistic style and narrative. However, the main points were evident in all of them.

To conclude, the reason for this blog piece – after reading through my writings a few times – is probably to serve as a brief manual on what it takes to actually pull through an audiovisual production on heritage.

"The Inclusive Museum": The Benaki's Museum Conference

What are the roles of museums and cultural institutions in society? Indeed, what will the museums of tomorrow look like? This topic, along with many innovative ideas, was presented Thursday, November 26, 2015 at The Inclusive Museum Conference sponsored by the Benaki Museum held at their Pireos Street Annex in Athens. Attended by 6 current members of the HERMA 2016 class, and several former members from last year, this day long conference included several forward-looking museum professionals from the United States and England.

Banner at event entrance

Karen Wong, Deputy Director of the New Museum in New York City kicked the day off with her visionary presentation. For those of you are not familiar with the New Museum’s collections please don’t be. They don’t have one! What they do have is IDEAS… and lots of them. In fact Ms. Wong co-founded the IDEAS CITY initiative which explores the future of cities with the belief that art and culture are essential to our future. The New Museum sponsors the first museum led incubator for art, technology and design. This incubator serves as a platform for entrepreneurs to collaborate and ultimately launch new ideas for a new world. Many of their innovative young thinkers have used the incubator to launch new cutting edge businesses in the arts and technology fields which have shown real gains to the economy through job creation. This initiative called NEW INC offers membership in return for office space and materials to work and creative license to soar. In the first year, these entrepreneurs produced 22 permanent jobs.

NEW Museum infograph, created by artists at the event

They have also launched “100 Ideas for the Future City.” This is a 6 day workshop brought to cities in need in collaboration with professionals from The New Museum that works to target issues, provide real solutions and then implement concrete actions. This workshop will be brought to Athens in September 2016.

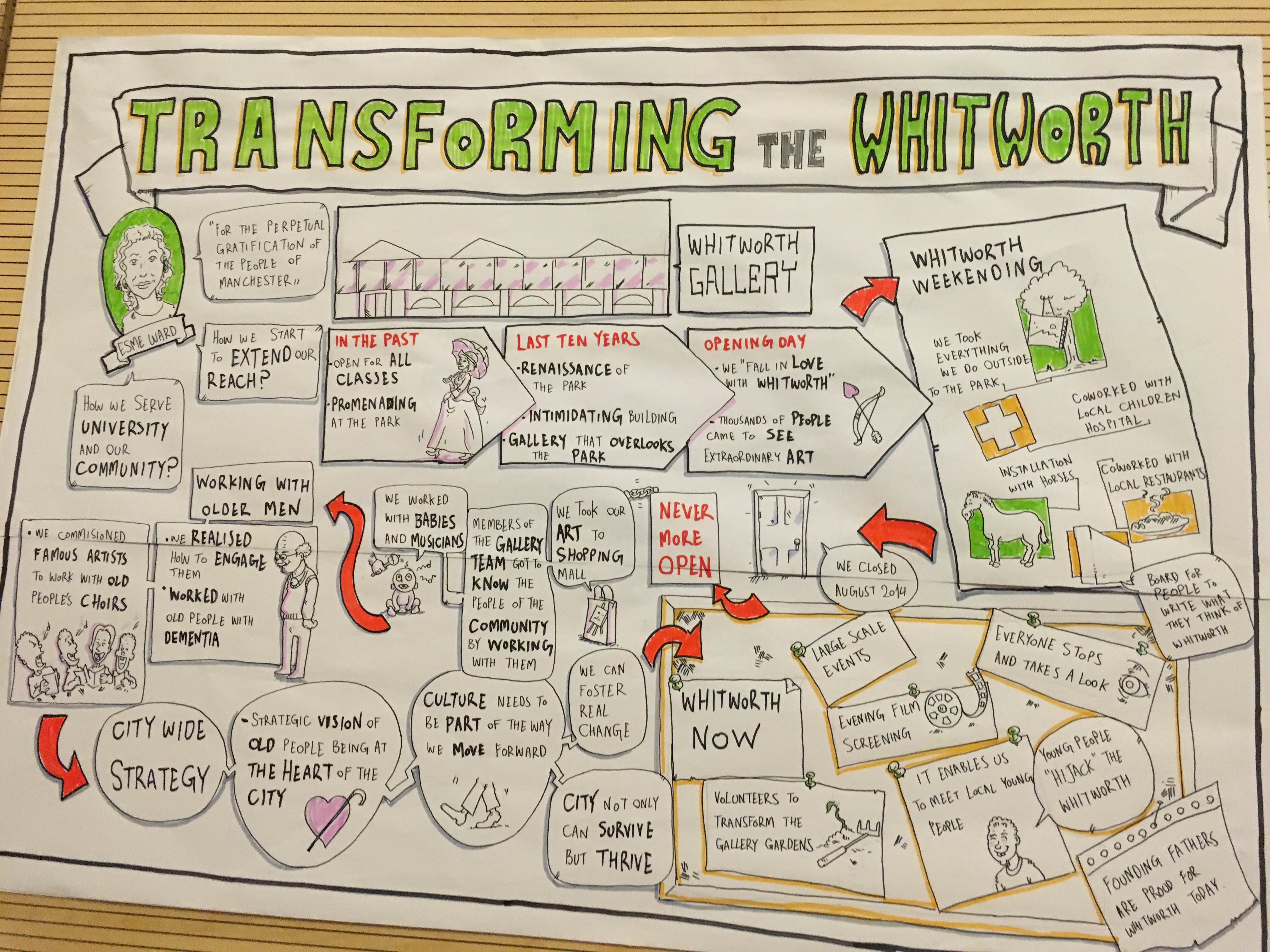

For those more traditional museologists, Esme’ Ward, Head of Engagement at Whitworth And Manchester Museum in Manchester, England spoke about the many inclusive changes implemented by her team at The Whitworth. The museum was transformed into a new space that includes the outdoor park adjacent to the museum. While undergoing development to the museum building the Whitworth team took a calculated risk and moved their collection outdoors! They invited all members of the community to come be a part of ” Whitworth Weekending” which was basically a picnic atmosphere in an outdoor museum combined with innovative exhibitions that delighted all ages. Not only did they enthrall the teenage audiences, but they even allowed those young future museum curators to plan and run the events. It’s risks like these that have won The Whitworth countless awards including Artfund Museum of the Year. A quote from the chair of Artfund, ” The transformation of the Whitworth has been one of the great museum achievements of recent years. It has changed the landscape: it truly feels like a museum of the future.”

Whitworth Infograph, created by artists at the event

An Internship with the Kuruma Marthudunera Aboriginal Coporation

Michael Williams:

MA in Heritage Management, University of Kent/Athens University of Economics and Business

Organisation:

Kuruma Marthudunera Aboriginal Corporation (KMAC)

Round: Summer 2015

Stream: Social Science

Long, empty expanse of red dirt, saltpans, mountainside, coastline, and a small package of civilisation neatly tucked in amongst it all. That was the scenery flying into Karratha airport, coupled with the town’s warm, humid embrace.

And it was pleasant from the beginning. KMAC’s Acting Cultural Heritage Manager Hannah Corbett picked me up from the airport, took me to buy groceries, helped me set up smoothly into my living environment, and drove me to work every day. Hannah was great at explaining the company and the Australian heritage situation at large, and was generally a very friendly person. The KMAC CEO Franklin Gaffney explained his directions very clearly from the outset, and continually offered insightful career advice. Also, all the people I met in the workplace were very friendly and welcoming.

Now to the work. One of the priorities of KMAC is to prevent mining companies taking advantage of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act 1972, which scan the Act for loopholes that allow them to utilise land that contains Aboriginal sites. One site in particular called the Robe River, has been recently deregistered and will soon be impacted by future projects. Coincidence? I think not. The Robe River is very important to the Kuruma Marthudunera (KM) people, and other Traditional Owners of the land that the river intersects. Its importance is shown not only as a provider for fresh water and habitat for a multitude of flora and fauna (many endangered), but also having spiritual significance of the Warlu (according to traditional owners the Warlu was a giant serpent whose movements through the area a long time ago shaped the landscape), which caused the shape and nature of the river. Without help the Robe River’s ecosystem, values, and significance will fall to the hands of the rich.

Hence, I was given the task of organising a large number of documents concerning the particular clause in the Act (Section 18) that determines the authorisations for land use, which in this case was specifically mining companies who’s work would ultimately impact the Robe River, and Bungaroo Creek. This involved tracking down evidence of: any misinterpretation of the act, mishandling of authority, missing information, and more. It also required the chronological organisation of information into an Excel spreadsheet, describing each piece of information in terms of its typology, content, authorship, and any other important information, including a summary of what each document actually says. It shed enormous light on the logistics of cultural heritage operations, and provided good initial practice working within an office environment.

I was also in charge of writing the KMAC newsletter. This involved tracking down and compiling information for KMAC’s December edition. This required searching through the KMAC information system, talking with KMAC staff, discussing traditional Kuruma language with one of the KMAC Aboriginal Heritage Officers, calling St John’s Ambulance for information and photos, stopping at a Christmas-style decorated tree on the side of a main road, taking photos of artefacts held in preservation with the KMAC office area, and other forms of information collection. Most of my time was spent writing the text and compiling an 11-page text and photos word document, which was sent to the company’s newsletter editor to be put into KMAC’s pre-defined business format.

I was given a variety of other tasks, such as: organising an Australian Archaeological Association membership for the KMAC Aboriginal Heritage Officer, organising reading portfolios for the KM Board Meeting, and copying documents related to the Robe River. Another assignment was to review, comment, and present a condensed report on the environmental impact of the West Pilbara Iron Ore Project mining extensions, and the construction of a Haul Road, by Australian Premium Iron Joint Venture (APIJV).

My last duty was to compile a high level breakdown of KMAC’s major Land use agreements, focusing on: the date the agreements were signed, the parties and people who signed the agreements, when the agreements were/are next up for renewal, the monetary conditions (including the required compensation to KM members) and non-monetary conditions of the agreement. The land use agreements were either “Claim Wide” (land use within the entire boundary of KM owned land) or based on the specific boundaries agreed to by particular projects or land tenements.

If there is was ever a perfect place to stay during an internship, it was here. I stayed in a separate room within a shared living complex in the beautiful Point Samson area. The room offered: air conditioning (perfect for the extreme heat), wireless internet, TV, bar fridge, large cupboard space, large bed, iron and ironing board, bedside tables, power board, built in bathroom, the works! Even better was the common area upstairs, which had a large kitchen with all necessary cooking apparatus, an even a bigger TV, comfy lounges, washing machine, clothesline, dishwasher, and a balcony with a view of the coast. The locals are all very friendly too, and one weekend we were even visited by a large group of Port Samson locals who were traveling from house to house to celebrate the Christmas holidays.

Initially, I spent my free time working on my MA thesis, or relaxing after a busy day’s work. The place is great to just put your feet up and unwind, and there is a fishing line to use, but unfortunately I really can’t fish! Nonetheless there is a beach up the road at Port Samson, the famous Honeymoon Cove, which has beautiful warm and clear water. There are plenty of fish and coral to see, so it’s a picturesque snorkel.

On the last night of the full moon Hannah, her boyfriend and I went to see the beautiful Staircase Moonlight from a lookout at Cossack. We had a beer watching the phenomena and met a real Aussie character who mentioned some nice pubs and fish restaurants close by. When my thesis was finally done we took trip to Millstream National Park, seeing the Millstream Homestead/museum, and taking a swim in Deep Reach pool along the Fortescue River, passing the Harding Dam on our way back to Port Samson.

Millstream National Park

The standout was visiting the Burrup Peninsula and finding lots of Aboriginal rock art/petroglyphs throughout an incredible and arduous journey in the 45-degree heat, with great views of the surrounding canyon-like landscape, and coming across many carvings of kangaroo, turtle, lizard, bird, fish, people, and other figures.

Aboriginal Rock Paintings

Burrup Peninsula Walk

I also went to Port Walcott Yacht Club for the last Sunday of the year (and until March 2016) in which they were selling their famous fish & chips, eating them with a great view of Cape Lambert. Close by were the massive stockpiles of iron ore that is kept near the jetty from which almost 20 large carrier ships wait their turn to transport it to their respective countries.

The last week featured KMAC’s Christmas party, and I was invited to come along. I was given a free three course meal with a couple of drinks included, which I enjoyed very much with the other friendly KMAC workers.

All in all, it was a great experience and I’d definitely recommend it to anyone.

Should you want to find out more about this project, or would like to enquire about an internship, please get in touch, using the information below:

Aurora Internship Program website: http://www.auroraproject.com.au/aboutapplyinginternship

Applications for the Winter 2016 round of Aurora internships will open online from 9am AEST Monday 7th March through to 5pm AEST Friday 1st April 2016.

Michael Williams, BA in Ancient History, GDip in Maritime Archaeology. Particularly interested in Maritime Heritage of the ancient Mediterranean. I have worked in Indigenous Aboriginal sites around New South Wales and in underwater sites in Port Macdonnell. Experience with archaeological drawing.

Michael Williams, BA in Ancient History, GDip in Maritime Archaeology. Particularly interested in Maritime Heritage of the ancient Mediterranean. I have worked in Indigenous Aboriginal sites around New South Wales and in underwater sites in Port Macdonnell. Experience with archaeological drawing.

Kisiwani Cultural Heritage Survey Excursion

During field research in the Kilwa District of Tanzania, I was invited to tour the island Kilwa Kisiwani. This provided the opportunity to conduct a survey of Kilwa Kisiwani’s natural and cultural heritage resources, and capture in-field data made up of observation, participation, and interview activities. The survey was named the Kisiwani Cultural Heritage Survey Excursion (KCHSE).

KCHSE objectives

- Survey and investigate the potential establishment of a coastal, archaeological, and/or cultural heritage tour for future visitors

- Discover a way to utilise the existing cultural heritage resources and practices, and provide new business opportunities for locals

- Meet, live, and experience the Kisiwani culture with locals

- Stay the night and experience their accommodation and hospitality

- Join local Kisiwani fisherman for morning fishing activities

- Explore the Kisiwani coastline from a snorkelling viewpoint

- Visit Kisiwani’s heritage and archaeological sites

- Meet some tourists/visitors to record their observations and opinions

The excursion

Saturday Afternoon

At 3:00pm my Field Study meeting with the Kilwa Kisiwani chairperson/chief was finished, and we were taken back through the Kiswiani village, and into the house of a local man known as Mr Bwanga. Like 90% of the population in Kilwa, he is of Muslim faith. I was told his name meant “football player”, in honour of his reputable sporting talent, and he now resides in the Kilwa District as a part time tour guide. Since my Field Study partner Revocatus Bugumba knew most of the residents (being the recent Kilwa Site Manager), I was able to be respectably introduced to the local residents, who were very welcoming and kind.

After walking into Mr Bwanga’s house, two men came in and sat down. They ended up being two local fishermen/farmers, one of whom, Abdullah, was very knowledgeable about specialised plants for medicinal purposes, which is of course very similar to that of other Indigenous people’s knowledge of their homeland, such as Australian Aborigines. We talked about their work, such as octopus fishing, which went along the lines of stabbing the octopus, and allowing it to grapple its tentacles around your arm while you continuously stab it in the head, “until it loses all its strength and cannot hold onto you any longer!” Abdullah said.

Inside Mr Bwanga’s house. (Left to Right Revocatus, Abdullah, Mr Bwanga, Abdullah’s friend, Acting Site Manager Paul Nyelo)

They told us that they were not always successful on fishing trips, and that they learned their craft purely from experience and being taught by more experienced fishermen irrespective of age (proven by Abdullah’s friend who had learned how to fish in his mid 20s). Fortuitously, after only a brief conversation, sparked by an idea from the meeting earlier, the men accepted me to join their fishing work for the following morning. I accepted while trying to hold back excitement. Also noteworthy was the service of tea from Mr Bwanga’s wife and daughter. It was made of peppermint, cloves, and ginger, which created a sweet, spicy, and minty taste. We returned to Kilwa Masoka (the mainland) soon afterwards.

Saturday Evening

In the evening I was taken back to island of Kilwa Kisiwani by two local Kisiwani men. crossing the channel on a traditional Dhow fishing boat, and watching the sunset.

Mr Bwanga, who is also an employee of the Tanzanian Antiquities Division at the Kilwa District level, sailed the boat with his son Abdullah accompanying us. Also on the boat were a group of other Tanzanians from Dar es Salaam. When I arrived I was taken up to Mr Bwanga’s house to drop off my bag, needing little grasp of the native Kiswahili language to understand the direction I was being led. Abdullah then began to usher me around the island, showing me the historic forts, Arabic school and facilities, and some of the many wells in Kilwa Kisiwani. He explained how the houses were built with coral rock and rocky mud that is used like cement. Every person I met were kind enough to say “Mambo” (hello) and “Karibu” (welcome) in Kiswahili. When I said “Shikamo” (a respectful greeting to elders), they replied with the respectful response “Ma-haraba”.

Abdullah continued the tour past the Great Mosque and then towards the German House. He spoke about the house being built in 1879, the time which the Kilwa District was ruled by the Germans for 33 years, and after a long line of different rulers beforehand over centuries. Abdullah lives in the German House as the village “Watchman”, a respectful position in charge of supervising the waters beyond the island, from the advantageous viewpoint that the German House offers. He welcomed me inside for a visit, also showing me the house’s magnificent back porch area. Also in the house was an English to Kiswahili dictionary, which assisted me greatly. I was able to say “Me-zaa” to express having fun, after which he went into an hysterical laughter, even telling his father about it the following morning. On the walk back I showed him the Southern Cross in the night sky, which amazed him, especially when I spoke of the significance of it being used for navigation to Australia by past sailors. I also played the card game “Uno” with him, which he played with complete freedom, making up his own rules on the way.

During the night I was sitting outside and was greeted by a very interesting local. He began teaching me some Kiswahili, particularly with the expression “toon-galley-kua pamodye”, which meant two people learning from eachother. He spoke with such animation, with wide open eyes, and an automatic responsiveness to everything I tried to communicate. I felt safe at all times, and they were very patient with me needing to regather my orientation in unfamiliar areas from time to time. The family provided me a dinner of rice, beans, sauce, and vegetables, accompanied by Mr Bwanga’s wife’s tasty tea. Following dinner, and after gazing at the incredibly clear night sky while allowing my food to digest, Abdullah said “Alarmsik” (farewell and goodnight), and went to his home quarters at the German House. I went to bed in my own room (thankfully with a mosquito net) in Mr Bwanga’s traditional African palm-leaved house, feeling an amazing sense of wonder at the very different world I was getting a brief but amazing taste of.

Sunday Morning

I was awoken and collected by Abdullah at 7:00am. At around 7:15, locals began gathering by the Kisiwani port in preparation for the morning’s fishing activities. Even though they knew absolutely no English to ask why I was with them, they seemed unfazed by my presence.

Eventually, about 8-10 men had gathered as the sun rose, and a light cool breeze filled the air. I stared in confusion at a man alone on a Dhow boat filling multiple large bags with sand, while cleaning other empty bags. He eventually saw me and welcomed me on board, where I was joined by Abdullah and one other young man.

During the sail out, I was given a plastic container to empty out water leaking into the boat, and after a approx. 10 mins we stopped at a big red buoy. We began pulling up the rope connected to the buoy onto the boat, including the attached anchor. It took about 20 minutes to pull the whole rope up, as it was constantly getting snagged by either the boat itself, or by shells, twigs, rocks, etc.

When the net becomes tangled, one of the men uses a paddle to rotate the boat clockwise or anti-clockwise in order to straighten it. This is where the prepared bags of sand are put to use, as they are all positioned on one half of the boat, so that the lighter half of the boat (without sandbags) can rotate more easily. After the entire net has come up and all the fish have been taken off, they drop the anchor, net, and buoy back in the water, while leaving the captured fish to flap about on the bottom of the boat until becoming still.

Traditional fish trap

When the wind picks up, one man erects the sail to propel the boat forward, while another men either steers with the rudder at the stern, or continues to empty out water from the boat. Afterwards, they sail up and down the coastline monitoring the clear water for any other fish that can be speared (using a metal rod as a spear).

While the search for fish is happening up and down the coastline, you are able to begin snorkelling. There are beautiful sights to see, with a multitude of different coral reef and fish species appearing every time you choose to dip down.

The water visibility is very clear, up to approx. 10 metres, and the water is nice and warm, approx. 22-26 degrees celsius. They allowed me to swim for almost 2 hours before returning to the port at 11:15am. On return, young Kisiwani boys can be seen fishing with hand lines from the main wharf.

At around 11:30am Abdullah continued the tour, showing me his personal house nearby the wharf. After 11 years he had almost completely built it, with only the concrete floor, and an added kitchen area to be done later. After leaving his house, we passed his Grandmother and Auntie’s housing area. Outside one of these houses I greeted 5 young boys, who were very shy yet excited to be meeting a foreigner. Abdullah pointed to a stone and demonstrated that it was a cooking tool by whirling his body like a tornado, which was one of the things he remembered us talking about the previous night.

After close inspection he started assembling what was actually a traditional Grinding Stone. He ushered me to try it, and after a few failed practice attempts he brought over the legitimate equipment used for grinding, and his Grandma brought out a bowl of rice. The device was very effective, with two very large and heavy round, circular stones used to smash up the rice, giving it a smooth, powdery consistency for their traditional cuisine (most probably “Ugali”). After giving all the kids high fives, a few of the villagers said “mambo”, including a different Abdullah, who I eventually recognised as the interesting man teaching me Kiswahili the previous night. A breakfast/lunch was then served back at Mr Bwanga’s peaceful little house, made up of delicious tea and cornflour pancakes.

Sunday Afternoon

A change of clothes after lunch was necessary for the afternoon’s walking around Kisiwani. Abdullah led me on a tour of the Kisiwani ruins, seeing: the Great Mosque, Makutani Palace and Ruins, the Dome Mosque, and Gereza Fort.

Abdullah gave a very knowledgeable dialogue on the heritage, history and archaeology, despite having very little grasp of English. This unfortunately meant that the tour dialogue was almost completely rehearsed, hence questioning him about certain aspects of the site was rather difficult.

On further observation, it was clear that the pathways and sites need to be cleared of grass. The sites should also be supervised daily to better direct visiting tourists, and to stop animals getting in and destroying the site. A group of goats had made their way inside the Gereza Fort area, and this should not be allowed to occur. Nonetheless, the tour was very peaceful and interesting, and I was able to meet two Tanzanian tourists at the Gereza Fort, who were happy to discuss my Field Study Project, and Kilwa Kisiwani’s conservation issues. They were also happy to provide contact details and fill out a questionnaire for research purposes.

After being provided lunch back at Mr Bwanga’s house, my stay had ended, and I was kindly directed towards the jetty to return back to Kilwa Masoko. I took a Dhow boat again, this time with a large group of older Tanzanian men and women. On arrival, Mr. Bwanga walked with me to a cafe to meet my study partner Revocatus, which officially ended the KCHSE.

Main outcomes of KCHSE

- The main outcome of KCHSE is the birth of the “Kilwa Kisiwani Heritage Trail”: a trail highlighted by a picturesque sailing and snorkelling trail, where you have the option to sail with, assist, and/or observe the local fishermen using traditional fishing vessels, techniques, and fishing equipment such as: fish traps, fishing nets, and dhow boats. The snorkel would be followed by a guided journey throughout the island of Kisiwani, enjoying all the cultural heritage it has to offer including Ruins of World Heritage Status. One can also be taken to Kisiwani’s ship conservation area, to receive an interesting explanation on traditional boat construction, Kilwa’s maritime history and culture, traditional fishing techniques etc., and could include the observation of ship building in practice.

View of Gereza Fort from boat

- The beauty of the tour is the ability to include extra heritage tour options, such as: “learn how to use a grind stone”, “take a tour of the archaeological sites”, and enjoying locally grown and prepared consumables such as pawpaw, coconut, juice, fish, etc. There could also be other exclusive experiences on offer such as “Prayer in the Great Mosque”, religious and cultural demonstrations/participation, playing a football match against a local Kisiwani football team, and many more. Such adaptability to visitor’s preferences makes the trail as unique and special an experience as possible.

- There can be many useful market research benchmarks to use during further development of the trail, such as Australia’s Great barrier Reef, Cambodia’s “Uncu Vet”, and Rome’s Palatine Hill.

Observations

- Tour guides need better English language skills

- The pathways and sites need to be cleared of grass so that the trail is more comfortable and visitor friendly

- Sites need to have daily on-site supervision for increased authoritative status, and to stop animals getting in and destroying the site.

- However, an increase of visitors to Kilwa Kisiwani from such tourism activities as presented in this document, could necessitate and financially support frequent site supervision, site cleaning, and path clearing of Kisiwani’s natural and cultural heritage resources.

- It will be a long time before SCUBA diving could be incorporated into the trail and operate profitably due to the scarcity and low quality of: technology, suppliers, resources, economy, and market.

Michael Williams, BA in Ancient History, GDip in Maritime Archaeology. Particularly interested in Maritime Heritage of the ancient Mediterranean. I have worked in Indigenous Aboriginal sites around New South Wales and in underwater sites in Port Macdonnell. Experience with archaeological drawing.

Michael Williams, BA in Ancient History, GDip in Maritime Archaeology. Particularly interested in Maritime Heritage of the ancient Mediterranean. I have worked in Indigenous Aboriginal sites around New South Wales and in underwater sites in Port Macdonnell. Experience with archaeological drawing.

HMO Communications workshop for Heritage Managers

You have organised the best exhibition of the year, or set up a ground-breaking educational program. You have worked hard with curators, conservators, educators, everything is ready to rock, but now you wonder… how can I bring people in? How can I reach my audience, and what should I be telling them? Informing and engaging the public is a crucial process for the success and sustainability of heritage institutions. However, heritage-related university programs do not usually include any training in Communications, and heritage managers who cannot afford to recur to external experts might find themselves in serious troubles when it comes to communicate and promote what they are doing.

This is why last April HMO organised the first Workshop in Communication Strategy for a group of 15 students from the joint MA in Heritage Management of the University of Kent and Athens University Business School. The workshop took place in Elefsina, a few meters away from the archaeological site of ancient Eleusis. The course instructor, Derwin Johnson, has a 20-year experience as a journalist for CNN and ABC, and is a professional media consultant and trainer.

The aim of the workshop was to give heritage managers the basic tools to communicate the identity, activities and events of their cultural organisation effectively in order to engage the right audience with the right messages.

Participants learnt how to produce a communication strategy, starting with identifying the appropriate audiences through a “conversation map”, where you can visualise all the groups interested in your message and select the most convenient for you. Once they knew who they were talking to, the students could then draft their key messages, the core ideas that they needed to express, and then learnt how to tweak those messages depending on the different media they wanted to use: more informal and experience-focussed for a blog, more simple and informative for a press release, more condensed and witty for social media. They had the chance to experiment with a wide variety of styles, always keeping an eye on the core message and reminding the importance of consistency.

A considerable amount of time was dedicated to interview simulations, where the students had to talk about their organisation in front of a camera and answer questions from Derwin playing the role of a journalist. They learnt how to catch attention and stay focussed on their messages, but also how to improvise in case of unexpected remarks.

The most successful feature of the course was that applied work immediately followed the theoretical lectures. Participants could put into practice what they just learned by working in groups under the supervision of the instructor, and receiving immediate feedback and further advice. A good example for that is the press conference simulation that took place on the last course day: each team had to present in a structured manner their piece of news to a (fake) audience of journalists ready to leave if they were bored or ask tricky and uncomfortable questions. It was a matter of coordination and team work, and students learnt the importance of being inspirational and audience-oriented when communicating their mission and messages.

Philanthropy, love of man – the HMO Fundraising workshop

Philanthropy is a word that dates back to the ancient Greeks and there is no better place to learn the true meaning and actions of the word than in Greece itself. The three-day workshop provided by the University of Kent’s Philanthropic centre took place last February in Elefsina, just a few kilometres from Athens. It was lead by Dr Triona Fitton, Dr Eddy Hogg and Dr John McLoughlin of the University of Kent, experts in the field of social policy, social research and sociology.

Philanthropy is part of the third sector, with more importance in some places than others. However, giving needs to be recognised as more than parting ways with money, but as a large system that encompasses and embraces all of humankind. A sector that brings people together, whether that be through volunteering, giving or asking. The fundraising workshop explained how this could be possible.

We learnt what we mean when we say philanthropy, why people and companies give, the core elements of fundraising, the different types of fundraisers and fundraising, and above all, how to make “the ask” and how to approach potential givers.

However, not all the workshop was lecture-based. We did post-it exercises on whether we personally give and why, and we participated in the debate of why heritage is a priority for fundraisers. On the last day of the workshop we were split into teams and were to pitch our own ways to fundraise for the HMO (the Heritage Management Organization) summer school programmes in Greece. All of which were great ideas and given the right amount of time can be implemented correctly.

Participation in this workshop did not go without merit. At the very end we were examined through the Institute of Fundraising online exam… and we all passed!

The workshop explained why fundraising is a well worth while thing to pursue, especially in the heritage sector, when heritage relies on the ‘love of man’ to be sustained. After three days of hard work and learning, the workshop had trained and gained 22 members of the Institute of Fundraising, all raring and ready to help many worthy causes.

Elizabeth Kearsey – BA in Classical Civilisation (University of Nottingham) now a student of the MA in Heritage Management. Lifetime student (so far). I am new to the work field of heritage, having previously worked with people with learning disabilities.

Elizabeth Kearsey – BA in Classical Civilisation (University of Nottingham) now a student of the MA in Heritage Management. Lifetime student (so far). I am new to the work field of heritage, having previously worked with people with learning disabilities.